|

|

|||

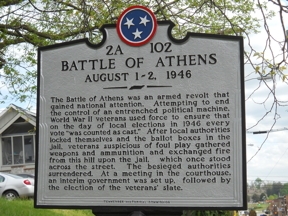

August 1, 1946, was election day in Tennessee. As we still do on the first Thursday in August, Tennesseans went to the polls.·

It was General Election day for judges and for county officials.

It was the Democratic and Republican primary elections for Governor and federal offices in advance of the General Election in November.

In Tennessee, the most visible elections are typically for Governor and Sheriff. That day’s ballot featured both.

In East Tennessee’s McMinn County, the day was turbulent from the beginning. County politics had fallen under the spell of a statewide political machine 10 years earlier in 1936. Corruption was pervasive.

In East Tennessee’s McMinn County, the day was turbulent from the beginning. County politics had fallen under the spell of a statewide political machine 10 years earlier in 1936. Corruption was pervasive.

Local resentment of police brutality and heavy-handed law enforcement had steadily escalated during this time and reached a fever pitch after GIs returned from World War II.

The GIs had organized a reform slate of candidates for local offices, especially sheriff. The veterans had dozens of armed poll watchers arrayed against the incumbent sheriff’s 200 deputies on duty, many from out of the county and some from out of the state.

Election Day in McMinn County featured shenanigans at the polls and even a shooting.

After the polls closed, an initial tally of the ballots showed the GI reform slate had won. Quickly, the sheriff and his men spirited the ballot boxes to the jail with the intention of altering the outcome.

The GIs fought for democracy in Europe and Japan, and they wanted democracy at home. They broke into the National Guard Armory and took 30-.06 rifles, Thompson sub-machine guns and bandoliers of ammunition.

The battle-seasoned veterans took up strategic positions around the jail, claiming the high ground overlooking the low-sitting hoosegow. The second floor of a bank building was the bastion of their front line.

Accounts of exactly how the shooting started vary, but all witnesses agreed that the fusillade of gunfire was withering, both from the veterans and from the deputies inside the jail.

The Chattanooga Times said “the former soldiers were pouring lead into every  opening in the brick jail.”

opening in the brick jail.”

Additional deputies trying to reach the jail and reinforce their comrades were turned back by bullets.

Estimates range as high as 2,000 attackers outside the jail, but the active shooters probably numbered in the hundreds. Fist fights broke out in the streets beyond the line of the bullets.

The rifle fire wasn’t enough to drive the deputies out, so the GIs began hurling Molotov cocktails. They couldn’t get close enough to the jail for those to be effective.

Then they started throwing sticks of dynamite. Those generally didn’t go farther than cars parked in front of the jail, flipping or destroying many of those.

Finally, a GI snuck up close to the jail with three dynamite charges. One destroyed the sheriff’s car, another took out the front porch of the jail and a third landed against a jailhouse wall and damaged it.

Meanwhile, the gunfire continued.

Several hours into the engagement, an ambulance arrived. The GIs held their fire for the evacuation of the wounded. As it turned out, however, the two occupants of the departing ambulance were the unscathed outgoing sheriff and the machine’s candidate for sheriff on the fateful day.·

The volleys continued until 3:30 a.m., when 60 deputies left their weapons behind and emerged from the jail under a white flag of surrender.

The volleys continued until 3:30 a.m., when 60 deputies left their weapons behind and emerged from the jail under a white flag of surrender.

Coverage of the event was on the front page of The New York Times for the next two days, although the first day’s story erroneously said two people were killed.

An honest vote tally showed that the GIs’ reform slate of candidates won the local elections overwhelmingly, but the implications were far greater than a local election. The events in McMinn County would begin a dramatic change in the course of Tennessee history.

It would become known as the Battle of Athens, and it would be the beginning of the end for a Memphis political boss known as the Red Snapper. The Red Snapper was Edward Hull Crump — today generally known as Boss Crump — and this is the story of his rise and fall.

It would become known as the Battle of Athens, and it would be the beginning of the end for a Memphis political boss known as the Red Snapper. The Red Snapper was Edward Hull Crump — today generally known as Boss Crump — and this is the story of his rise and fall.

Boss Crump dominated — some say controlled — Tennessee politics· for the middle third of the 20th Century. The Battle of Athens was a tipping point, but it would take another six years for him to be vanquished at the ballot box, and this is that story.

Ed Crump came to Memphis in 1893 at the age of 19 from Holly Springs, Mississippi. The economy was in the pits, and he got a job clerking at a Memphis cotton company. He quickly began dabbling in Democratic politics and was a delegate to the Democratic state convention several times in the first years of the 20th Century.

Ironically, he was part of a reform slate in Memphis. Led by a maverick named William Wellford, the reformers were crusading against Memphis Mayor J.J. Williams, who governed over a corrupt regime.·

Crump won election to the Board of Public Works, which was the lower house of a bicameral city government. He and his running mates presented themselves as “a properly conservative businessmen’s ticket for thinking people,” in the words of Crump biographer William Miller.

Crump won election to the Board of Public Works, which was the lower house of a bicameral city government. He and his running mates presented themselves as “a properly conservative businessmen’s ticket for thinking people,” in the words of Crump biographer William Miller.

The reformers won up and down the ballot, but the reform was rather short-lived. Memphis’ culture of booze, prostitutes and gambling was barely affected.

In his first public office, Crump made a valiant effort to be a progressive reformer, but he was thwarted at every turn by the Memphis power structure, emerging principally as a gadfly.

Frustrated and disgusted, he resigned from the Board of Public Works after less than two years. He put his business affairs in order and launched an outsider’s campaign for the Fire & Police Commission, which was the upper legislative body.

By all accounts, Crump was a vigorous campaigner, outworking his opponents. Building on his previous credentials as a reformer, he made public ownership of utilities for the public benefit a centerpiece of his campaign. Crump won by nearly a thousand votes, and an enthusiastic celebration ensued.

As a side note, he had to make a quick detour to the city jail on election night to vouch for and secure the release of an out-of-town supporter who’d celebrated too much. The miscreant was a Bible and sock salesman from Louisiana named Huey Long.

Once he was sworn in as one of five Fire & Police Commissioners, Crump became a headline-grabbing reformer. He led deputies on gambling raids to undermine the prevailing Memphis pretense that crimes of immorality didn’t exist and engaged in a public feud with the police chief.

Crump became a leading advocate for restructuring Memphis city government by the Tennessee General Assembly and in 1908 organized a slate of candidates for the Legislature from Memphis committed to that goal.

Crump’s “People’s Democratic Ticket” to represent Memphis in Nashville won, and the next year the Legislature passed a bill changing Memphis to a six-member governing commission.

Later in the same year – 1909 – Crump announced he would be a candidate for mayor of Memphis, and he would be running against his old nemesis, former mayor J.J. Williams.

Later in the same year – 1909 – Crump announced he would be a candidate for mayor of Memphis, and he would be running against his old nemesis, former mayor J.J. Williams.

Crump was a credible public speaker, but he primarily relied on a combination of surrogates at public events and self-written newspaper ads, a technique he used throughout his career.

He remained an unapologetic reformer, advocating for public ownership of utilities and against corporations, especially those that owned parallel steel rails.

Crump was elected mayor by 79 votes in a hotly contested election. Despite 11 lawsuits over the results, former Mayor Williams’ chief counsel finally asked for the complaints to be dismissed and acknowledged that the outcome was fair and honest.

Crump’s service as mayor began well enough, but less than five years later the future political boss had begun to emerge. The Crump administration was aggressive with tax collections, civic improvements and public works, but the bawdy houses, saloons and gambling continued unabated.

Prohibition was a roiling issue in the era before the 18th Amendment banned demon rum. It often dominated state political campaigns and led to the assassination in Nashville of former U.S. Sen. Edward Carmack, whose statue oversees the Tunnel entrance to the State Capitol today.

Prohibition was a roiling issue in the era before the 18th Amendment banned demon rum. It often dominated state political campaigns and led to the assassination in Nashville of former U.S. Sen. Edward Carmack, whose statue oversees the Tunnel entrance to the State Capitol today.

Crump’s resistance to enforcing the law culminated with a state ouster law that could be directed against public officials who didn’t enforce liquor laws. Enforcing liquor laws in Memphis was political anathema to the majority of the city’s population, but popular sentiment didn’t prevent an individual from filing an ouster lawsuit, which someone did.

Subsequently, Crump lost the ouster lawsuit, won re-election as mayor while the ouster proceedings were on appeal, won a battle over whether he could be seated for another term despite being ousted, was sworn in for that term, collected his back pay and immediately resigned in favor of a hand-picked successor.

It was a typical episode in Memphis politics.

Leaving the mayor’s office in 1915 was just the start of another chapter for Crump, though. He set his sights on more distant quarry and began expanding his influence statewide.

During the next 20 years— from 1915 to the 1930s — Crump built a statewide organization. Relentless campaigning, attention to detail and constant networking steadily increased his influence.

He supported enfranchisement of African-Americans, often paying poll taxes for them because they were a reliable voting bloc.

One of his lieutenants in the Memphis black community was funeral director N.J. Ford, whose offspring John Ford, Emmett Ford and Ophelia Ford would later serve in the Legislature. N.J.’s son Harold Sr. and grandson Harold Jr. served in Congress. Ford Family

Crump was a staunch Democrat, but he included Republicans in his coalition when they helped his cause. Gradually, he became an influential force in statewide politics. By the early 1930s, his support could virtually elect a governor or a U.S. Senator.

He had little reason to worry about one Senate seat, though, because Sen. K.D. McKellar of Memphis was a long-time crony from Crump’s earliest days in Memphis politics and will return later in this story.

Crump rarely held office himself, although he spent two terms in Congress from 1931 to 1935. He was an ardent New Dealer in support of President Roosevelt, but he didn’t enjoy it.

Washington was too far removed from his power base in Memphis, and it would be a long time before he could be as important in D.C. as he was in the Bluff City. In 1934, Crump announced he wouldn’t run for re-election to Congress.

He hand-picked his congressional successor and came home. As a leading ally of FDR, he had plenty of public works projects and patronage to distribute during the New Deal, further enhancing his power.

He lived the slogan of FDR’s chief political operative James Farley: “Early to bed; early to rise. Work like hell and organize.”

Typically, he traded away federal patronage in Republican East Tennessee and didn’t support Democrats for local office in that region in exchange for the support of East Tennessee Republicans in statewide matters.

In other words, you could pick the postmasters and the agricultural extension agents, if your county delivered for Crump candidates on Election Day. It was a corrupt bargain satisfactory for all concerned.

During the 1930s and through World War II, Crump was the absolute boss in Tennessee politics. He had his detractors, especially the Memphis Press-Scimitar and The Tennessean newspapers, but challenges to his rule nearly always failed.

During the 1930s and through World War II, Crump was the absolute boss in Tennessee politics. He had his detractors, especially the Memphis Press-Scimitar and The Tennessean newspapers, but challenges to his rule nearly always failed.

Crump controlled the Democratic primaries, and Tennessee was overwhelmingly Democratic in statewide elections. The state went 50 years — from 1920 to 1970 — without electing a Republican governor, and Howard Baker in 1966 was the first Republican senator since popular election of senators began in 1916.

The Red Snapper won election after election by hook or by crook. He’d substitute candidates at the last minute, install candidates to split the opposition vote and lash out through newspaper ads that bordered on libelous without crossing the line.

Typical was the 1939 election for mayor of Memphis. Crump’s candidate was an incumbent congressman who couldn’t come home to campaign. So Crump ran for mayor himself without opposition and was elected. In the first minutes of January 1, 1940, he was inaugurated as mayor on the back of a passenger train in a snowstorm before departing for the Sugar Bowl.

He immediately resigned, making his vice mayor the mayor. The vice mayor quickly resigned, creating a vacancy in the office of mayor, and City Council later the same day picked another Crump crony as mayor.

Memphis had four mayors in 24 hours.

It was this political machine that took control of McMinn County politics in 1936 and maintained control of an increasingly corrupt government until the Battle of Athens 10 years later.

Resentment and opposition to Crump machine politics wasn’t limited to McMinn County, though. That was the flashpoint. Led by returning GIs, the mood statewide was in favor of political reform.

Estes Kefauver of Madisonville was elected to the U.S. House in 1939 from the 3rd Congressional District in the southeast part of the state. The 3rd District, coincidentally, included Athens and McMinn County.

Yale-educated Kefauver was a good-government progressive and also a strong supporter of Roosevelt, but not for the same reasons as Crump. Kefauver philosophically believed in the New Deal and the hope and promise it brought for impoverished East Tennessee. And Kefauver opposed machine politics.

He supported the Tennessee Valley Authority and successfully opposed Crump and Senator McKellar, who wanted TVA jobs to be patronage jobs. Kefauver was a populist advocate for small business against big corporations. He worked to strengthen the Federal Trade Commission and close loopholes in the Clayton Antitrust Act.

He was exactly the kind of clean politician beyond Crump’s control that Crump couldn’t stand.

With a decade of hard work in Congress behind him and a reformer’s attitude — and high awareness of sentiments represented by the Battle of Athens two years earlier — Kefauver decided that he would run for the U.S. Senate in 1948.

He’d thought about running against Senator McKellar in 1946, but several of Congressman Kefauver’s allies persuaded him to wait two years for a less formidable opponent.

The other U.S. Senator was Tom Stewart of Winchester, who’d been installed by Crump 10 years earlier. Crump had come to regard Stewart as ineffectual and disloyal, and the boss’ organization informed Stewart that he wouldn’t receive their support in 1948.

Instead, Crump would support Judge John Mitchell of Cookeville.

Stewart was undeterred, however, and announced that he would run for re-election even without Crump’s support. Stewart’s decision to run despite Crump would prove to be pivotal.

It meant that Kefauver would be running in the Democratic primary against two Crump candidates – the erstwhile Sen. Tom Stewart and the newly anointed Judge John Mitchell.

This would play to Kefauver’s advantage because the Crump bloc would effectively be split. Senator Stewart still had his loyalists, and Crump was backing Judge Mitchell.

In the same election year, former Gov. Gordon Browning decided to run for his old office. He served one term in the 1930s with the blessing of Crump and lost a campaign for re-election after alienating Crump with good government.

Browning compiled a distinguished record as an officer in World War II and entered 1948 highly regarded through the combination of his military service and his previous term as governor.

With the reform wave building, Browning announced he’d run against Crump acolyte Gov. Jim McCord in the August 1948 Democratic Primary.

The stage was now set: Congressman Kefauver against Senator Stewart and Judge Mitchell for the U.S. Senate and former Governor Browning against Governor McCord for Governor.

Crump’s political power, his credibility and his statewide machine faced their supreme test.

The candidates crisscrossed the state, primarily by automobile, through the spring and summer of 1948. Roads were often unpaved, and most of the cars were un-air conditioned. Newspapers were the dominant media of the day, and every big-city daily took sides.

Reporters traveled with the candidates constantly, often sharing a car and bunking at the same motel. Radio was the only other form of mass communication that mattered, and candidates would drop by for interviews in between popular music and ads for Granny Loomis sausage and Martha White flour.

In early June, Crump published one of his trademark newspaper screeds. He accused Kefauver of being a pet raccoon for Communists. He said Kefauver was “a darling of Communists and Communist sympathizers.”

In early June, Crump published one of his trademark newspaper screeds. He accused Kefauver of being a pet raccoon for Communists. He said Kefauver was “a darling of Communists and Communist sympathizers.”

Crump said Kefauver “reminds me of the pet coon that puts its foot in an open drawer in your room, but invariably turns its head while its foot is feeling around in the drawer. The coon hopes, through its cunning by turning its head, he will deceive any onlookers as to where his foot is and what it is into.”

The Cold War and anti-Communist sentiments were still escalating, and this could be a devastating blow to Kefauver’s campaign if it stuck.

Two weeks later, Kefauver went to the heart of Crump’s stronghold for a campaign dinner at the Peabody Hotel in Memphis. It was his first campaign trip to the boss’ lair.

It was possibly the most dramatic moment in Tennessee political history in between the Battle of Athens and the early inauguration of Lamar Alexander as Governor in 1979. Kefauver said in Memphis:

“This animal — the most American of all animals — has been defamed. You wouldn’t find a coon in Russia.

“It is one of the cleanest of all animals; it is one of the most courageous. … A coon … can lick a dog four times its size; he is somewhat of a “giant-killer” among the animals.

“Yes, the coon is all-American. Davy Crockett, Sam Houston, James Robertson and all our great men of that era in Tennessee history wore the familiar ring-tailed, coonskin cap.

“Mr. Crump defames me, but worse than that he defames the coon, the all-American animal. We coons can take care of ourselves. I may be a pet coon, but I ain’t Mr. Crump’s pet coon.”

The Kefauver campaign adopted the raccoon as a mascot. Supporters sent live raccoons to Kefauver headquarters. His speechwriters inserted raccoon references in his speeches. A typical line said, “a coon has rings round its tail, but this is one coon that will never have a ring through its nose.”

The Kefauver campaign adopted the raccoon as a mascot. Supporters sent live raccoons to Kefauver headquarters. His speechwriters inserted raccoon references in his speeches. A typical line said, “a coon has rings round its tail, but this is one coon that will never have a ring through its nose.”

Crump’s candidate, Judge Mitchell, was a colorless campaigner and making no headway on the hustings. Incumbent Senator Stewart didn’t want to alienate Crump in case Crump abandoned Mitchell in mid-campaign for a last-ditch effort to re-elect Stewart, which Crump reportedly considered.

Congressman Kefauver rightly made Crump the central issue in the campaign. He goaded Senator Stewart to say something against Crump, which Stewart wouldn’t do.

Kefauver tried to trap Stewart and Mitchell in person to challenge them on Crump, and they went to extraordinary lengths to avoid a faceoff. Once, Mitchell went so far out of his way to avoid Kefauver that he was discovered campaigning in northern Alabama.

Kefauver repeatedly suggested Crump would switch from Judge Mitchell to Senator Stewart, effectively tarring both opponents with the political boss and making it increasingly difficult for Crump to make a switch.

Meanwhile, Browning was running hard against Governor McCord and also making Crump an issue.

Meanwhile, Browning was running hard against Governor McCord and also making Crump an issue.

In East Tennessee, Browning implored voters to support his “great crusade to end dictatorship in Tennessee and move the capitol from Memphis back to Nashville, where it belongs.”

Browning said McCord “can’t draw a breath unless he gets permission from the dictator in Memphis.”

Incumbent Gov. McCord was suffering around the state for backing the state’s first sales tax. Browning said McCord wasn’t being aggressive enough in expanding government to solve Tennessee’s problems, pointing to roads as an example.

This put the incumbent in the awkward position of being criticized by people opposed to any sales tax at all and also by those who believed he hadn’t gone far enough. It was a narrow middle ground.

Browning did a masterful job of engaging Crump in a public debate through the newspapers, further cementing the public’s perception that the election was a referendum on Crump.

Crump’s newspaper broadsides included this terrific quote. “Browning has about as much chance to beat Jim McCord on August 5th as a one-legged grasshopper has in a turkey field.”

In another ad, Crump said, “In some respects Browning is a very, very bad man. In others, he is worse.”

From Washington, Senator McKellar endorsed Crump’s ticket of Judge Mitchell for Senate and Governor McCord for re-election, but in the field much of McKellar’s organization continued to work to re-elect Senator Stewart.

The Tennessean, the Memphis Press-Scimitar, the Knoxville News-Sentinel and the Chattanooga Times all strongly endorsed Kefauver and Browning.

August 5, 1948 — two years after the Battle of Athens — Crump’s machine suffered a pair of crushing defeats on the same day. Kefauver and Browning each won the Democratic nomination in his respective race.

Foreseeing the turbulence on the Democratic side, the Republicans had nominated candidates, including country music star Roy Acuff for governor. It was 1948, though, so President Truman’s coattails in a Democratic state combined with the overwhelming good will for beating Crump assured that Kefauver and Browning won in November.

Just like Robert E. Lee after Gettysburg, though, this huge defeat didn’t mean Crump was finished. His compatriot K.D. McKellar still held the other Senate seat, and Crump entertained visions of a comeback one day.

Tennessee governors then served two-year terms. Browning had to run for re-election in 1950, but he wasn’t opposed by Crump and won another two-year term fairly easily.

And that brings us to 1952, six years after the Battle of Athens. Browning would run for another term as governor, and McKellar would be on the ballot again in pursuit of his seventh six-year term in the U.S. Senate.

And that brings us to 1952, six years after the Battle of Athens. Browning would run for another term as governor, and McKellar would be on the ballot again in pursuit of his seventh six-year term in the U.S. Senate.

An up-and-coming Dickson lawyer named Frank Clement entered the race for Governor. Clement wasn’t recruited and sponsored by Crump, but Clement was a vehicle for Crump’s revenge.

Meanwhile, a seven-term Congressman from Carthage named Albert Gore Sr. announced he would run against McKellar and, by inference, Crump.

Again, the election was a donnybrook with mixed loyalties, full-page newspaper ads and accusations of Communism, Crumpism, cronyism and everything except botulism.

The 82-year-old McKellar distributed signs that said, “Thinking Feller Votes McKellar.”

The Gore campaign placed signs next to McKellar’s that said, “Think Some More And Vote For Gore.”

McKellar’s biggest hindrance was his age and declining health. Gore was a vigorous campaigner who looked great on the new medium of television. McKellar campaigned little and was visibly infirm when he did.

McKellar’s biggest hindrance was his age and declining health. Gore was a vigorous campaigner who looked great on the new medium of television. McKellar campaigned little and was visibly infirm when he did.

Crump had suggested to his friend McKellar that he retire, but the old bachelor would have none of it. Many pundits said that Crump put most of his effort into Clement’s campaign against Browning, tacitly abandoning his old ally.

The same reform-minded newspapers that backed Kefauver and Browning in 1948 backed Gore.

In the August 1952 primary, Congressman Gore defeated Senator McKellar in a landslide. Crump achieved his revenge on Browning by helping to elect Clement, but the election was his last hurrah.

Crump died of natural causes two years later in 1954, and any lingering influence of his political machine effectively died with him, ending a major era in Tennessee political history.

Lord Action said that power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Never was that more true than with Boss Crump. He began as a reformer, but the more power he accumulated the more corrupt he became.

Lord Action said that power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Never was that more true than with Boss Crump. He began as a reformer, but the more power he accumulated the more corrupt he became.

After World War II, he contradicted the ideals for which we fought the war, and he was cast aside by a younger generation with higher expectations.

And that is the story of the demise of the Red Snapper.