|

|

|||

The Middle Tennessee Railroad was one of the shortest-lived railroads in the State of Tennessee. Its corporate history spanned the years 1909 through 1928, but in that short period of time a tradition of southern hospitality and a spirit of genuine determination was reflected in its daily operations.

The railroad was an outgrowth of a blossoming mining industry in Tennessee, specifically the phosphate mines of south central Tennessee. The Middle Tennessee Railroad, taking a longer route to serve two cities that were already connected by rail, simply had to fail. It was a lesson in redundancy, but at the same time, a tribute to the determination of a man who wanted to be a railroad tycoon, even if he did have to buy his own railroad back from his creditors.

The railroad was an outgrowth of a blossoming mining industry in Tennessee, specifically the phosphate mines of south central Tennessee. The Middle Tennessee Railroad, taking a longer route to serve two cities that were already connected by rail, simply had to fail. It was a lesson in redundancy, but at the same time, a tribute to the determination of a man who wanted to be a railroad tycoon, even if he did have to buy his own railroad back from his creditors.

The phosphate industry in Middle Tennessee was in its infancy at the beginning of the 20th Century. In Maury County, phosphate rock was discovered about a mile and a half south of Columbia in 1888 by a stonecutter named William Shirley who noticed an odd-looking rock in an outcropping on a hillside there. An assessment of this rock showed it to be rich in phosphorous, a discovery that was to change the history of the area for decades to come.

The flurry of mining activity that began transformed the south central part of the state into a mining center, rivalling that of the Gold Rush days of California a half century before. The rock that stonecutter Shirley found was phosphate rock known as “brown rock,” an ore rich in phosphorous. Other types of phosphate, such as the lower grades of “white rock” and “blue rock” were also found, but these lower grades were mainly confined to the Highland Rim area of Tennessee centering on Hickman and Lewis counties.

The flurry of mining activity that began transformed the south central part of the state into a mining center, rivalling that of the Gold Rush days of California a half century before. The rock that stonecutter Shirley found was phosphate rock known as “brown rock,” an ore rich in phosphorous. Other types of phosphate, such as the lower grades of “white rock” and “blue rock” were also found, but these lower grades were mainly confined to the Highland Rim area of Tennessee centering on Hickman and Lewis counties.

Although mining operations were set up in the Centerville area, the discovery of the higher grades of brown rock in Maury County eventually made these blue rock mines unprofitable. Actually, the Maury County deposits of phosphate rock were among the largest in the United States, being on the same scale as the massive deposits in Florida and Idaho.

The area in northwestern Maury County around the community of Leatherwood contained sizable deposits of blue phosphate rock also. The Leatherwood area was well known for its phosphate beds, but it was not accessible by rail, so it was uneconomical to begin mining operations there at that time. In 1905 a large tract of land owned by the Tennessee Fertilizer Company near there was sold to the Independent Phosphate Company for the purpose of mining out the phosphate rock.

The Tennessee Fertilizer Company was owned by J.H. Carpenter and J.W. Howard, who agreed to provide rail service to the land at a competitive price. They first tried to negotiate with the L&N to build a branch to Leatherwood, but this was to no avail. Finally, Carpenter decided to build the railroad himself. This was the beginning of the Middle Tennessee Railroad.

Probably no other business venture better symbolized the spirit of optimism of American enterprise than building a railroad. Railroads at that time were the primary means of transporting virtually everything, and the social and economic life of a town centered around the depot. Although Mr. Carpenter's Middle Tennessee Railroad was to be a branch line into the wilderness, at the same time it was a gamble on prosperity — prosperity that would be about as permanent as the blue rock of the Leatherwood mines.

On October 25, 1907, the Middle Tennessee Railroad was chartered as a corporation with J.H. Carpenter as its president. The corporation was authorized to build a 28.7 mile line from Franklin to Leatherwood. Tracklaying began from Franklin in July 1909. The track gangs encountered little difficulty, and the track to Leatherwood was completed in March of the next year.

On October 25, 1907, the Middle Tennessee Railroad was chartered as a corporation with J.H. Carpenter as its president. The corporation was authorized to build a 28.7 mile line from Franklin to Leatherwood. Tracklaying began from Franklin in July 1909. The track gangs encountered little difficulty, and the track to Leatherwood was completed in March of the next year.

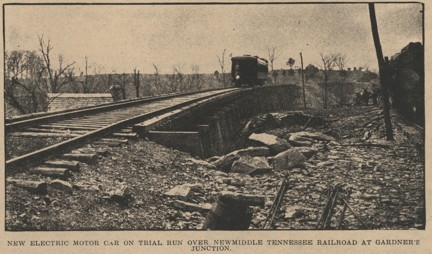

It is remarkable that the trackage was completed so quickly since a tunnel had to be built near Leatherwood, as well as several long trestles nearby. A connection was made at Franklin with the Nashville Interurban Railway to forward freight to the Tennessee Central Railroad at Nashville. Mr. Carpenter did not build a connecting track to the L&N at Franklin until several years later.

At the very time that the Middle Tennessee began operations, the deficiencies of blue rock were just becoming evident. The far superior brown rock deposits of the Mount Pleasant area were making the Leatherwood operations less economical with each passing day. The Independent Phosphate Company subsequently became interested in mining in Mount Pleasant and offered to give the Middle Tennessee Railroad a good amount of traffic if Mr. Carpenter would extend his railroad to that town.

Carpenter, realizing that the life of his railroad was directly related to the life of the mines, knew his little railroad had to expand or expire. Subsequently, he made plans to expand his railroad in the direction of Mount Pleasant.

Lacking the enormous amount of capital that was required to extend his railroad empire, he requested a bond issue from Mount Pleasant in the amount of $100,000 to finance the building. The city council, disgusted with the Louisville & Nashville's handling of the phosphate boom, heartily agreed. Rich again, Carpenter made plans to go south for the rail traffic his railroad so desperately needed.

The L&N had acquired a line through Columbia and Mount Pleasant that was built by the Nashville, Florence & Sheffield Railway at the time of the Civil War. This was a rail line linking Nashville with Sheffield, Ala., and was bought by the L&N before 1900. Indeed, the L&N enjoyed a virtual monopoly on all rail shipments in the Maury County area by the turn of the century since it also now controlled the Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis Railroad, which had a branch to Columbia via Lewisburg (formerly the Duck River Valley Narrow Gauge Railroad).

The captive market enjoyed by the L&N in Maury County meant that it really didn't have to provide any incentives to get the carloads of phosphate rock since it was the only feasible way of shipping the rock, and there was no competition. The mine operators around Mount Pleasant soon became incensed over the treatment by the L&N. This arrangement was not very popular with the general citizenry either. The Mount Pleasant Chronicle spared no effort to blast the L&N for its actions:

“The Louisville and Nashville Railroad has treated this industry with manifest unfairness notwithstanding the fact that its earnings are increased by over $600,000 per year by shipments from Mount Pleasant alone. … Not one dollar has been spent by the railroad company except for absolutely necessary track room and scales at the depot, and for the depot itself. All shippers who want a track must grade it, pay cash (for the track components) … giving a deed to the railroad company for the right of way. … This is in marked contrast with the same road in Birmingham, where they have been known to put in a track to get freight, without even waiting to get the shipper's consent. Such is life on a branch railroad without competition, when you are in the phosphate business.”

Therefore, it is not surprising that the new railroad was greeted with open arms as the construction crews made their way through the hills and valleys from the north. Carpenter could not have had a more receptive audience than the mine operators of Maury County.

As mining operations sprang up virtually overnight, activity around Mount Pleasant blossomed to healthy proportions for such a small town. Fortune seekers from all over the country poured into Maury County eager to purchase mineral rights to just about any land and dig for the phosphate that lay buried only a few feet from the surface. Farms around Mount Pleasant that for decades had been practically worthless now commanded top prices as news of the boom circulated.

In 1896, the population of Mount Pleasant was only 500. However, by 1899, this once sleepy town had swelled to 2,000. At that time, the editor of the Mount Pleasant Chronicle boasted that he was "willing to bet a nickel to a ginger cake” that the population of the city would reach 8,000 in three years.

Certainly, a town of this magnitude was going to need another railroad. Carpenter selected a point on his railroad about five miles east of Leatherwood (thereafter called “Leatherwood Junction”) and began building in a southerly direction toward Mount Pleasant around the end of 1910.

Page 1