|

|

|||

A Tale of Two Cities in the Same County is a story about political extremists fomenting domestic unrest with a little violence. It also has a tiny bit of unrequited love, though nothing as dramatic as in Charles Dickens’ two cities. Neither does my story include death, the Bastille or the guillotine.

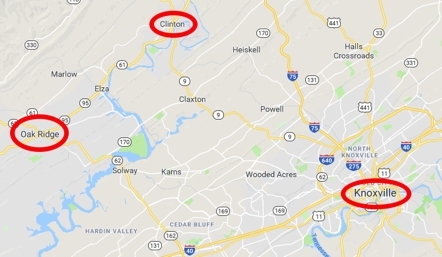

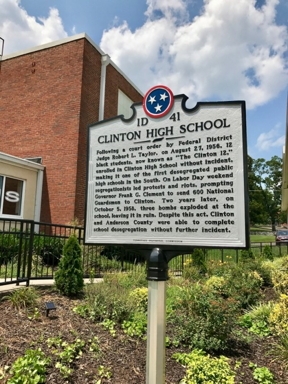

The county is Anderson County, Tennessee, and the cities are Oak Ridge and Clinton, which were among the first school systems in the nation to confront the issue of school desegregation in the 1950s.

It is incredibly ironic to me that two cities in the same county would play such a pivotal role in such a seminal moment in American history. And although they are only 11 miles apart, each city reached the world stage by a completely different path. Each city was barely incidental to events in the other.

It is incredibly ironic to me that two cities in the same county would play such a pivotal role in such a seminal moment in American history. And although they are only 11 miles apart, each city reached the world stage by a completely different path. Each city was barely incidental to events in the other.

Most of us are familiar with the broad outlines of the history in both cities, but I undertook this project with two goals.

First, I wanted to know more about the details of what happened in Oak Ridge and Clinton.

Second, I wanted to understand the events in both cities in the context of the larger timeline of civil rights and school desegregation throughout the country.

To put it another way, we all know parts of these stories, but I will try to fill gaps between the parts we know while placing these events in the larger picture.

To pick a slightly arbitrary starting point … at the end of World War II, the 1896 case of Plessy v. Ferguson was the law of the land with regards to racial segregation. Plessy put forth the standard of “separate but equal” that upheld segregation.

We all know that the Supreme Court ruled in the 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education case that segregated schools are unconstitutional because they violate the principle of equal protection under the law. “Separate schools are inherently unequal,” the court famously pronounced.

That was on May 17, 1954.

In September 1954, two small school systems in northwest Arkansas – Fayetteville and Charleston – became the first school systems in the Confederate South to desegregate. It happened quietly and without much fanfare.

Oak Ridge High School, my alma mater, desegregated in September 1955 … 15 months after Brown v. Board of Education. It was peaceful, which I’ll describe in more detail in a minute.

Five months later in January 1956, Miss Autherine Lucy attempted to enroll at the University of Alabama. After a series of missteps on both sides of the issue, Miss Lucy was ultimately barred from The University of Alabama, ostensibly for reasons other than race.

Immediately thereafter in February and March of 1956, a group of Southern congressmen signed the Southern Manifesto, pledging to use all means possible to fight desegregation.

Among those who refused to sign were both Tennessee Senators – Estes Kefauver and Albert Gore Sr. – and the Congressman who represented Anderson County – Howard Baker Sr. In fact, less than half of the Tennessee delegation signed the Southern Manifesto.

Five months after the Southern Manifesto, in August 1956, Clinton High School desegregated with the participation of the Tennessee Highway Patrol and the Tennessee National Guard. I’ll also flog that subject more in a little bit.

Five months after the Southern Manifesto, in August 1956, Clinton High School desegregated with the participation of the Tennessee Highway Patrol and the Tennessee National Guard. I’ll also flog that subject more in a little bit.

One year after Clinton, Nashville desegregated. The Hattie Cotton Elementary School was bombed on Sept. 10, 1957. The walls of segregation in Nashville began to crumble in earnest the next day.

Little Rock Central High School occurred at the same time as Nashville … a year after Clinton … two years after Oak Ridge. President Eisenhower sent federal troops to keep the peace and uphold the court in Little Rock.

For further context, James Meredith was admitted to the University of Mississippi with the support of the U.S. Army in 1962, which was five years after Clinton.

But Oak Ridge and Clinton preceded all of those major events.

Now let’s study Oak Ridge in some detail.

You probably know that Oak Ridge is a city created by the federal government during World War II to process uranium for the first two atomic bombs. At the dawn of 1942, the area was nothing but farmland. At the end of 1943, it was a city of 100,000 people, the fifth largest city in Tennessee.

The U.S. government built everything in Oak Ridge, and it owned everything. Everyone who lived in the city worked for the federal government or for a government-approved business that provided goods or services to the residents. This was all operated under the Atomic Energy Commission.

The AEC paid for everything … the government fixed the plumbing in your house, managed the hospital and paid for the police and fire departments. Until 1952, the government even decided who could come into town.

There were no local taxes. Most important, the Atomic Energy Commission paid for and ran the school system.

The AEC also ran school systems in two other atomic cities … Los Alamos, New Mexico, and Richland, Washington. Those school systems were desegregated before Brown vs. Board of Education.

Moreover, during the 1952 presidential campaign, Dwight Eisenhower had answered a question at a campaign event by saying that all schools on federal reservations should be desegregated.

Oak Ridge was not technically a federal reservation, but the implications of Eisenhower’s remarks for Oak Ridge were clear. Yet few Oak Ridgers were bothered by the prospect of desegregated schools.

That’s because when the federal government created a city of 100,000 people in a year’s time, it wasn’t just picking people at random. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which directed the Manhattan Project during the war, had recruited a highly educated populace.

In the mid-1950s, Oak Ridge had the highest concentration of Ph.D.s per capita of any city in the United States. Desperate for so many scientists and engineers, Oak Ridgers had been recruited from all over the country to come work on a secret war project. There was nothing southern about this city in the South.

Oak Ridge was built as a segregated city because the federal government wanted to respect Tennessee law, which required segregation. The Army’s objective was to process uranium in the middle of a war, not to re-engineer social policy in the foothills of Tennessee.

African-Americans lived in a part of Oak Ridge called Gamble Valley and had their own elementary school, junior high school and high school. Those schools were not equal to the schools for white students.

Eight months after Brown v. Board -- in January 1955 -- the Atomic Energy Commission announced that Oak Ridge High School and Robertsville Junior High School would be desegregated in September of the same year. About 100 black students would be transferring to the previously all-white schools.

As it turned out, the AEC had been quietly planning the move for two years.

As it turned out, the AEC had been quietly planning the move for two years.

The dramatic announcement caused a lot of talk but very little objection, as reported the next day by the daily newspaper, called The Oak Ridger.

Several days later, The Oak Ridger editorialized, “Integration is a necessary and desirable move towards making democracy stronger.”

Planning proceeded during the spring in a low-key manner and without controversy. An African-American teacher named Fred Brown was hired, so the teaching corps was to be integrated, too.

When teachers convened in August to begin their pre-school preparations, The Oak Ridger reported that School Superintendent Bertis Capehart “called for a climate of ‘kindness, consideration and respect’ in dealing with this first year of a local integrated school system.”

Capehart called for teachers to lead by example and teach students that successful interpersonal relationships with different types of people are important.

Everything continued to be quiet until Sunday, September 5, which was the day before schools were to open. On Sunday, mimeographed circulars began to appear in some neighborhoods calling for a boycott of school on Monday to protest integration. The flier referred to a group called Oak Ridgers for Segregation, but only one person stepped forward as a member.

The opening day of school, September 6, proceeded normally. At the student assembly marking the opening of school, Oak Ridge High School Principal Tom Dunigan tried to set the tone. He said, “I shall strive to see all individuals first as human beings and respond to their personalities before responding to their race, color or religion.”

The proposed boycott was seen as ineffective.

Enrollment at the high school and at Robertsville Junior High School was lower than the previous year. But the largest cause was probably the fact that Oak Ridge was still shrinking from its wartime population of 100,000 to a population of roughly 28,000 by the late 1950s.

When school opened that year, the number of occupied housing units in the city was down by 650 from the year before. That was the proximate cause for the drop in enrollment.

A week after the successful opening of school, Oak Ridgers for Segregation announced it was dropping its boycott and was urging its members to return their children to school. No effect from the boycott was ever reported, so presumably it was inconsequential.

The Oak Ridger reported that the head of Oak Ridgers for Segregation said it would be “formally joining the Tennessee Federation for Constitutional Government and that it will be known from now on as the Oak Ridge branch of the TFCG.”

The Tennessee Federation for Constitutional Government was an anti-integration group based in Nashville and was led by Professor Donald Davidson of Vanderbilt, who had been one of the Agrarians. The Tennessee Federation for Constitutional Government will surface again in Clinton.

Going back to Oak Ridgers for Segregation, President C.A. Golden said, “We have asked the parents to send their children back to school because we realize that in keeping them out we are placing an additional burden on the teachers and also creating a hardship for the students.”

Meanwhile, another character had emerged in connection with this pro-segregation group. John E. Roy said “Our purpose is to prevent violence. We don’t want demonstrations of any kind. We want to fight integration as hard as we can but only by legal means.”

And that was pretty much the end of segregation in Oak Ridge schools. The all-black elementary school was closed as part of a general school consolidation and construction program in the 1960s, and black students were assigned to all of the city’s other elementary schools.

Meanwhile in the county seat of Clinton a different story was unfolding.

Outside of Oak Ridge, Anderson County was a rough-and-tumble county. It was an active part of the Crump political machine. It was the site of the Coal Creek War of 1891 and 1892 over the use of state convicts in coal mines.

Anderson County paid two adjoining counties – Knox and Roane -- to which it bused students for purposes of segregation. Citizens had sued to desegregate the schools in 1950 in a case called McSwain v. Anderson County.

Federal judge Robert Taylor of Knoxville turned them down, essentially on the basis of Plessy v. Ferguson, saying that the separate system of education required by state law was constitutional as implemented by Anderson County.

The McSwain case was bouncing around in the federal appellate system when Brown v. Board was announced. McSwain was remanded to Judge Taylor, who reversed his position based on Brown v. Board.

In January 1956, Judge Taylor ordered that Anderson County desegregate its schools in September.

Significantly, the local Anderson County elections in 1956 were to be the death throes of the political machine that had controlled the county. Several new officials were swept into office, including a new sheriff, and that would prove to be a blessing and a curse in September.

For most of the year, organized resistance to Judge Taylor’s order took the form of additional court filings, none of which were persuasive to the judiciary. Clinton was proceeding smoothly toward integration.

When it was time for school to start, the main pending legal action was a lawsuit filed in Chancery Court by the Tennessee Federation for Constitutional Government – the group headed by Professor Donald Davidson of Vanderbilt.

That lawsuit sought to withhold state funds from Clinton because desegregated schools would violate the Tennessee Constitution. Among its primary arguments was that Brown v. Board was unconstitutional, which to a non-lawyer like I seems hopeless on its face.

Better still, the weekly Clinton Courier-News quoted several of the alleged plaintiffs to the effect that they hadn’t authorized the use of their names as plaintiffs and wanted to be taken off the lawsuit.

Clinton residents might not all have been excited about integration, but no one seemed to want to cause any trouble.

Unfortunately, fate was about to drop a troublemaker named John Kasper into the situation.

Kasper was from New Jersey and graduated from Columbia University. He’d owned a bookstore in the Washington, D.C. neighborhood of Georgetown. In August 1956 … the month before Clinton started school … he formed the Seaboard White Citizens’ Council in Washington, D.C. He was a friend and disciple of Ezra Pound, advocate of American fascism.

Kasper became a vagabond for segregation, traveling to hot spots in the South and causing trouble.

His first stop was Charlottesville, Virginia, which was also scheduled to desegregate in the fall of 1956. In short order, he began distributing literature, disrupted a meeting and was arrested. As soon as he got out of jail, he headed to Clinton.

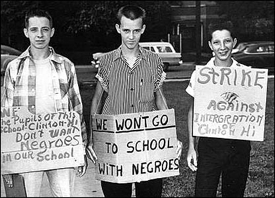

Kasper arrived in Clinton on Saturday, August 25. School was scheduled to begin the following Monday. Kasper began going door to door in the town of 3,700 people seeking protesters who would picket the high school on Monday and urging parents to keep their children home in a boycott.

By Sunday afternoon, Kasper was in jail for violating Judge Taylor’s order that no one was to interfere with desegregation in Clinton.

Despite Kasper’s efforts and with him still under arrest, Clinton High School opened normally on Monday morning with record enrollment and a small handful of pickets who departed embarrassedly after about five minutes. Twelve African-American students were enrolled, and the first school day proceeded peacefully.

Kasper was released on Tuesday morning, whereupon he went directly to Clinton High School and demanded that Principal D.J. Brittain resegregate the high school or resign. Brittain did neither.

Kasper then organized public rallies on the courthouse square to oppose integration. The rallies began to attract a few people, though many were from out of town. Picketing at Clinton High School in the morning increased, and the crowds were more agitated each day.

Groups that came to Clinton included the Tennessee Federation for Constitutional Government (again), the Pre-Southerners, the States’ Rights Council of Tennessee, the Tennessee Society to Maintain Segregation and the White Citizens’ Council of Tennessee.

Groups that came to Clinton included the Tennessee Federation for Constitutional Government (again), the Pre-Southerners, the States’ Rights Council of Tennessee, the Tennessee Society to Maintain Segregation and the White Citizens’ Council of Tennessee.

The rallies, however, were in defiance of Judge Taylor’s order. Kasper went to jail again within just a few days.

On Thursday of the first week of school, the Anderson County School Board reiterated its support of Principal Brittain and his handling of the crisis, but school attendance was dropping dramatically.

On the same day, Editor Horace Wells of the Clinton Courier-News denounced Kasper on the front page of the newspaper. I want to quote at length from the column.

The trouble this man Kasper is creating will serve only two purposes — to line his pockets with membership fees he will collect and turn this community upside down — bringing headlines through the country, headlines that will make it practically impossible to interest new industries to come and locate here, that will drive away people who might want to come here and build homes.

This country of ours was founded upon the Constitution — and Kasper would have you throw away the Constitution. He calls others communists, but he is using the very same tactics they use, and the end result of his efforts — should they be successful — would be mob rule, and that is just what the Communists would like, too.

While Kasper has a perfect right to come to Clinton, it is our opinion that so long as he his here he will cause trouble and grief.

It’s interesting to note that while the Oak Ridge newspaper had argued on the basis of elevating democracy, the Clinton newspaper was trying to appeal to economic interests and anti-Communism. Nonetheless, they were each shining a light in the right direction.

Kasper might have been in jail again, but the damage had been done by Friday night of the first week of school. It was the beginning of the Labor Day weekend, and tensions were becoming high.

A large crowd gathered at the courthouse. The Anderson County Sheriff’s Department had eight officers and was joined by the Clinton Police Department of eight more. They were no match for an angry mob of 1,500 people, and on Friday night rioting broke out in Clinton.

Blacks in automobiles were assaulted, and the mob moved as if to attack the home of the mayor, who was upholding the rule of law. Minor damage occurred, but late at night things quieted down.

Blacks in automobiles were assaulted, and the mob moved as if to attack the home of the mayor, who was upholding the rule of law. Minor damage occurred, but late at night things quieted down.

Needless to say, the town was a little tense when Saturday dawned.

During the day, Chancellor Joe Carden turned down the lawsuit to withhold state funding. Local and state officials prepared to maintain order on Saturday night. The sheriff and the city council continued to hope that they could handle the situation.

Governor Frank Clement wouldn’t act unilaterally, but he told officials in Clinton they could count on state support if they asked for it.

And at this point, I’d like to interrupt this narrative briefly to say that I think Frank Clement is clearly a hero of this story. Unlike governors in other Southern states who used their power in an attempt to thwart federal law and thwart desegregation, Clement was steadfast in support of order and the rule of law and integration.

There is no evidence that Clement ever wavered or hesitated to support desegregation. The previous January he’d faced down a segregationist march on the State Capitol, and he’d previously stopped segregationist bills in the Legislature.

On Saturday, he authorized state forces to go to Clinton if requested by local officials. His commitment to Clinton was solid, and as you’ll see in a minute, the outcome was dramatic.

But, again, the hope in Clinton on Saturday was to keep it under control locally.

To augment the sworn officers of the law, the sheriff organized and armed a citizens’ militia to preserve order. People began to gather in Clinton at about 6 p.m. Saturday, and within two hours 2,000 people were out of control.

Realizing he couldn’t contain the situation, the Sheriff contacted state officials. Within 30 minutes, 100 state troopers in 39 patrol cars descended on Clinton. They were under the command of Greg O’Rear.

For those of you unfamiliar with Greg O’Rear, he was about 6 feet, 8 inches tall and weighed about 300 pounds. He was a true mountain of a man who’d begun as a trooper on a motorcycle and would eventually be state Safety Commissioner. I knew him in his later years when he was Chief Sergeant at Arms of the Tennessee House of Representatives.

It is said that O’Rear emerged from a patrol car in Clinton that Saturday night with a double-barrel shotgun over his shoulder, announced loudly, “It’s over. Y’all go home,” and the crowd dispersed.

It is said that O’Rear emerged from a patrol car in Clinton that Saturday night with a double-barrel shotgun over his shoulder, announced loudly, “It’s over. Y’all go home,” and the crowd dispersed.

On Sunday morning, National Guard troops assembled at Crossville and proceeded to Clinton with a breakfast stop at Brushy Mountain State Prison. The guardsmen began to arrive in force at about 2 p.m., relieving the troopers who had been on duty overnight.

Under the code name of “Operation Law and Order,” 645 men in 100 vehicles took control of Clinton. They arrived to do business with seven M-41 tanks, three armored personnel carriers and a helicopter. The guardsmen were under the command of Adjutant General Joe Henry, who would later be Chief Justice of Tennessee.

U.S. Marshal Frank Quarles of Knoxville stood on the school steps and read a Federal Court order putting all Clinton area residents under a federal court injunction.

The deployment of the National Guard proceeded smoothly on Sunday afternoon, and the situation in Clinton was tense but calm with crowds of citizens milling about.

Now, do you remember that in my opening I promised you an unrequited love interest? Well, here it comes.

Into this tense situation, an African-American sailor from Knoxville named John Chandler strolled down the street in Clinton alone. He would later explain that he’d come over to court a girl. He knew there had been a little bit of trouble in Clinton, but he didn’t realize what he was getting into.

A mob set upon Chandler and chased him into a service station where a single National Guardsman protected him until reinforcements could arrive. Guardsmen with loaded rifles and fixed bayonets dispersed the crowd. Apparently Chandler didn’t get to see the girl.

When schools reconvened on the Tuesday after Labor Day, attendance was at a low point, but normalcy began to return. Attendance at Clinton High School rose steadily and substantially, although it would never reach the level of opening day.

When schools reconvened on the Tuesday after Labor Day, attendance was at a low point, but normalcy began to return. Attendance at Clinton High School rose steadily and substantially, although it would never reach the level of opening day.

The National Guard stayed on the scene until late September, but there were no further problems.

The Clinton crisis received worldwide news coverage because it was the first significant violence in opposition to integration after the smooth openings in Arkansas and in Oak Ridge.

The Associated Press, United Press, the International News Service, Life magazine, Time magazine, U.S. News and World Report and the Ladies Home Journal had reporters on the scene … altogether there were 76 reporters from as far away as London, England. Edward R. Murrow would come to Clinton for a special report.

Mail and telegrams poured into Clinton from around the world from people offering advice about the situation … sent to all manner of public officials and civic leaders. A fan sent Principal Brittain $5 “to buy himself a gift such as a necktie, a steak dinner or a pint of whisky.” He returned the money to the donor.

The astute among you are probably wondering, though, what about the bombing? I thought they bombed the high school, you’re thinking.

That’s right, but it was two years after the riots. The situation at the high school had proceeded smoothly in the meantime. In the fall of 1958, however, an estimated 75 to 100 sticks of dynamite leveled most of Clinton High School. No significant events preceded the bombing, and no one was ever prosecuted.

For two years after the bombing, Clinton High School convened in an idle elementary school in Oak Ridge while Clinton High School was rebuilt.

John Kasper, the trouble-making segregationist, would continue to be an agitator.

He was released from jail again in 1956 after the riots were over, but he didn’t go back to Clinton. Instead, he headed to Florida to spread his special brand of civic engagement. That proved to be a major miscalculation. The Florida Legislature started an investigation of Kasper.

The investigation revealed that back in his days of running the bookstore in Georgetown, Kasper had associated with blacks of both sexes at his bookstore and sometimes hosted interracial parties.

Well, this was heresy among the racists he was trying to lead. An Alabama state senator said Kasper was a “double agent, planted by race-mixers to discredit the entire resistance movement.”

None of the other segregationists wanted anything to do with him. He was now discredited within his own movement.

Kasper showed up in Nashville in September 1957 to organize opposition to desegregation here. I think he was in town when Hattie Cotton Elementary was bombed, but he was never linked to the crime.

He was jailed here for disturbing the peace, but he was released for insufficient evidence. When he walked out of the jail, federal officials took him into custody to serve 15 months in a Tallahassee federal prison for violating the court orders in Clinton.

Finally, I want to close by citing some of the heroes of this story:

Finally, I want to close by citing some of the heroes of this story:

First, was Governor Frank Clement. Throughout his career, Clement attempted to assert a moderate, progressive stance on integration and race relations. He thwarted segregation bills in the Legislature and acted forcefully in support of the rule of law in Clinton.

Two newspaper editors are heroes – Dick Smyser, editor of The Oak Ridger, and Horace Wells, editor of the Clinton Courier-News. Both editors steadfastly supported desegregation, albeit with different rationales and in different circumstances. Their voices for restraint were very important.

The local elected officials in Clinton were heroes. Many of them, including the sheriff, were new to public office, because of the purge of the political machine in elections only a few weeks earlier. But they acted in unison to do the right thing and didn’t try to appeal to their citizens’ lower motives, as did officials in Arkansas, Alabama, Mississippi and elsewhere.

And, finally, an enormous number of common, everyday citizens were heroes because they respected the law and their fellow citizens in the interest of public order and decency. Overshadowed by a few rabble-rousers, they held their communities together and helped to chart a course that looks undeniable only in hindsight.

To those heroes I dedicate my remarks.