|

|

|||

There were several formidable natural obstacles to achieving a terminal at Mount Pleasant, not the least of which was a necessarily long bridge over the Duck River and its flood plain. Fortunately, no tunnels were needed, since it was possible to follow the valleys along the edge of the Highland Rim for much of the way.

The Mount Pleasant Daily Advertiser reported on August 8, 1911, that the bridge across the Duck River had been completed, and the tracklaying was in progress in the community of Sawdust just south of there.

When the track gangs reached a farm owned by Wiley Harris just outside of Mount Pleasant however, things slowed down. The railroad and Mr. Harris could not agree upon a right-of-way through his property, but after a few days of haggling, an arrangement was made and the track crews resumed their push to the south.

Soon the tracks were laid into the outskirts of town and the townspeople were brimming with pride at having two railroads at last in their fair town. The front page of the Daily Advertiser of October 28, 1911, told the story:

Soon the tracks were laid into the outskirts of town and the townspeople were brimming with pride at having two railroads at last in their fair town. The front page of the Daily Advertiser of October 28, 1911, told the story:

“The new railroad is here. The tracklaying now has reached the point near the old race track in the city limits, where the depot will be built as rapidly as possible, and the construction train pulled in at noon today, it being the first train to come in over the new road.”

The excitement in the town was demonstrated by the huge celebration that was being planned for the railroad's arrival in town. Speeches by prominent city and county officials, free barbecue, free rides, and a brass band were on the minds of everyone in town as news spread of the near-completion of the Middle Tennessee. A meeting was called at a local bank to plan the party, attended by a great many townspeople, live wires every one of them. But the enthusiasm of the partygoers was dampened a bit by the news that the railroad was unfit for service owing to the hasty construction methods that were used to save money.

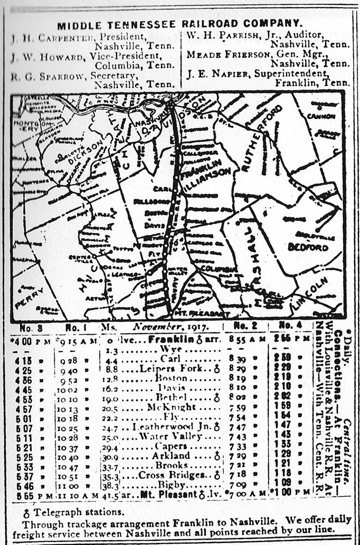

Indeed, it was well into May of the next year before regular trains were to run over the entire length of the Middle Tennessee. When it was completed, the Middle Tennessee Railroad consisted of 41.5 miles of track between Franklin and Mount Pleasant, plus a four mile branch to Leatherwood from Leatherwood Junction (see map).

The tracks skirted around the north and west sides of Franklin and headed in a southwesterly direction through Southall and Leiper's Fork. It followed Leiper's Creek as far as Fly in northern Maury County. There the tracks made a sweeping turn to the south following the valleys of the ridges that were generally south.

The tracks crossed the Duck River just north of Arkland on a substantial steel truss bridge and continued through Cross Bridges and on to Mount Pleasant, generally following the Bigby Creek for the final few miles.

In Mount Pleasant, the tracks cut a diagonal path through town, taking out a wing of the Southern Hotel on Columbia Avenue, and passing right by Blanchard & Biffle Undertakers. The line continued on through town to reach some of the outlying phosphate mines, and in the process crossed the L&N Swan Creek Branch (that ran from Mount Pleasant to Gordonsburg) just west of Swan Creek Junction.21 The good citizens of Mount Pleasant finally got to have their railroad party on May 15, 1912. The railroad gave free rides, politicians did some campaigning, there was plenty of free food, and everyone generally had a good time.

As the Middle Tennessee settled down to the business of railroading, it published its first official schedule. The schedule consisted of two round trip passenger trains between the two terminal towns, plus freight trains on an irregular schedule as needed. Generally, one freight train made a trip over the entire length of the railroad each day, and extras were run if needed.

The Leatherwood branch apparently did not have formal passenger trains as such, but local patrons sometimes hopped rides on the branchline freights. An arrangement was made with the Nashville Interurban Railway at Franklin to forward passengers on to Nashville. As of May 1912, the schedule was as follow:

TRAINS NORTH |

||

TRAIN |

LEAVES MOUNT PLEASANT |

ARRIVES NASHVILLE* |

2 |

7:00 a.m. |

10:00 a.m. |

4 |

2:00 p.m. |

5:00 p.m. |

TRAINS SOUTH |

||

TRAIN |

LEAVES NASHVILLE* |

ARRIVES MOUNT PLEASANT |

1 |

8:00 a.m. |

10:55 a.m. |

3 |

4:00 p.m. |

7:00 p.m. |

*via connection with Nashville Interurban Railway at Franklin |

||

This schedule was arranged so that only one set of passenger equipment was needed on the Middle Tennessee Railroad, since only one passenger train was on its own lines at any one time, an important consideration for dispatching purposes as well as equipment buying.

Economy in operation was definitely a top priority. For a time, the railroad used a portion of the offices of the Petrified Bone Phosphate Co. in Mount Pleasant for an agent’s office. Work on the depot progressed somewhat slowly and it was not finished until the summer of 1912. Track expansion in and around Mount Pleasant continued for a couple of years, with tracks reaching several of the major phosphate operations there.

Franklin, Leiper's Fork, Bethel, Leatherwood Junction, Arkland, Cross Bridges, and Mount Pleasant all had telegraphs in the depots for communication, with the center of operations being Franklin.

The Middle Tennessee Railroad, at one time or another, owned a total of four locomotives. The smallest of these, number 5, was an 0-4-0 switcher locomotive that was purchased secondhand and later wound up on the Tennessee Central. Two more locomotives, 4 (a 4-4-0) and 12 (a 2-8-0) were also bought used.

The only one that was bought new was the 25, a 4-6-0 built by Baldwin Locomotive Works in 1911. The 25 was the Middle Tennessee Railroad's big engine, and after the MT's demise, it was traded around on several railroads and eventually wound up on the St. Louis & San Francisco Railroad as its number 75.

The Middle Tennessee owned a grand total of four passenger cars, and a small fleet of freight cars, perhaps numbering 60. Most of these were gondolas used as ore jennies, but there were also boxcars, flat cars and some non-revenue maintenance equipment.

J.H. Carpenter must have realized early on that his railroad was in trouble. It was not a railroad that was ill-planned, but it was rather an unfortunate set of circumstances that rendered the Middle Tennessee obsolete as soon as it was built. Simply put, the L&N already had track in all the right places to keep the MT in red ink almost from the start. Although building the line from Franklin to Leatherwood was a logical step, as was the subsequent expansion to Mount Pleasant, the line as a whole was a lesson in redundancy, paralleling the L&N line a few miles to the east for its entire length.

Having no connection to other friendly railroads (the L&N being a fierce competitor) except for the Nashville Interurban Railway, he knew that further expansion was necessary to survive. Another complication was the fact that the Nashville Interurban could not accept heavy freight shipments owing to its light construction.

An extension through Mount Pleasant to a connection with the Southern Railway at Huntsville, Alabama, via Southport and Pulaski was under active consideration for some time. This would have made the Middle Tennessee Railroad a viable through route, as well as an added benefit of giving the railroad access to the phosphate fields in Giles County in the vicinity of the Wales community. Another possibility that was rumored was to tie the MT into a railroad that was being planned between Nashville and Corinth, Mississippi (tentatively named the Nashville, Shiloh & Corinth Railroad).

This would have given Carpenter's road a connection with the Southern Railway as well as the [Mobile & Ohio] at Corinth, thereby making his road feasible. Unfortunately, however, these grandiose plans were never realized, and the Middle Tennessee remained a railroad to nowhere, linking two towns by rail that were already connected. Once in operation, however, the Middle Tennessee Railroad was definitely a railroad with class.

The two daily passenger trains were a blessing to those who lived back in the hills along the route, as the roads in that area were impassable if they existed at all. The conductor, Mike Howard, was always willing to stop anywhere to let somebody on or off. When blackberries were ripe, the train would often stop along the route so the passengers and crew could stock up.

The two daily passenger trains were a blessing to those who lived back in the hills along the route, as the roads in that area were impassable if they existed at all. The conductor, Mike Howard, was always willing to stop anywhere to let somebody on or off. When blackberries were ripe, the train would often stop along the route so the passengers and crew could stock up.

Near Fly, the tracks cut through a hillside that exposed a free running spring. it was customary for the train to stop here at the spring so the passengers (who had endured a bouncy, cinder ridden ride) could refresh themselves and regain composure.

Always trying to accommodate, the conductor would announce each station along the line, as was customary on larger railroads. Near Boston there is a tiny community known as Mobley's Cut, so called because of a large trench dug through a hill so that the tracks could cut through a hill without going around it. One fine morning as the train approached Mobley's Cut, conductor Mike Howard stepped in from the vestibule of the swaying passenger car, and announced “Mobley's Cut.” Startled, an elderly woman indignantly demanded, “Well who in the (expletive deleted) cut Mobley?”

Although Mr. Carpenter had intended for phosphate to be the life blood of the Middle Tennessee, his railroad was quickly bleeding to death. Phosphate loadings never approached a level that made the Middle Tennessee Railroad a paying proposition.

Page 2